Policymakers miss Iowa's persistently poor neighborhoods

Longstanding poverty has a grip on select urban Iowa areas

In Iowa, when we talk about economic decline these days, it’s mostly about farm country.

There’s a good reason for that. The population of rural Iowa is shrinking. Main streets are struggling. Young people are leaving because they can’t find jobs.

Five years ago, Gov. Kim Reynolds created a task force to empower rural parts of the state. The Legislature has devoted significant resources to the effort, too.

But when it comes to the most persistent pockets of high poverty in the state, you won’t find it in rural Iowa; instead, it’s found in Iowa’s urban communities — in places like Waterloo, Des Moines and Davenport.

Need proof?

A recent US Census Bureau report found that not a single one of Iowa’s 99 counties met the definition of “persistent poverty,” meaning a place where the poverty rate has been at least 20% for 30 years (between 1989 and 2019). But when government statisticians drilled down to census tracts – more localized areas with populations of between 1,200 and 8,000 people – they found 39 in Iowa that met the criteria.

Nearly 110,000 Iowans live in these places.

The good news is Iowa had a smaller share of its population (3.6%) living in these persistent poverty tracts than most states.

But it’s not an insignificant number. If all 110,000 of these people lived in one county, it would be the sixth largest in Iowa.

In many cases, like Davenport, these historically impoverished areas are located in or near central cities, far away from the neighborhoods where growth is occurring. In other words, they’re neighborhoods some people never see.

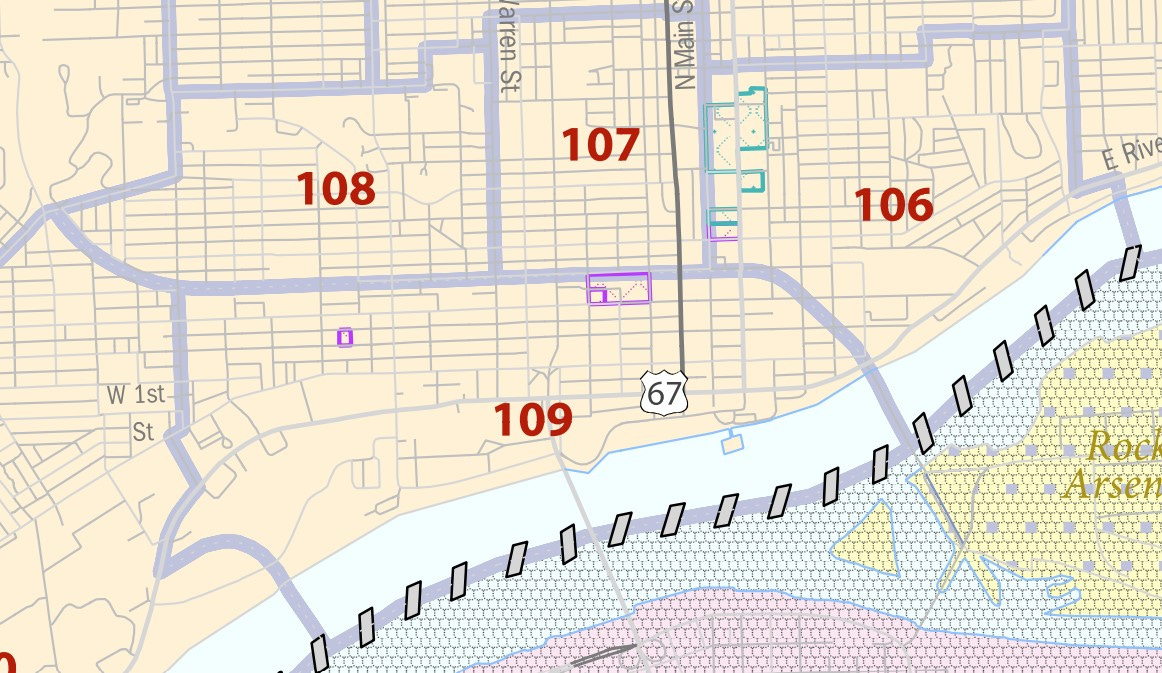

In Davenport, these persistent poverty tracts extend from Division Street on the west side to Bridge Avenue on the east, running south from roughly 12th Street to the Mississippi River.

These are some of the oldest parts of Davenport.

In government parlance, they’re census tracts 106, 107, 108 and 109.

These neighborhoods are old, they’re shrinking in population, and they’re disproportionately Black.

There are pockets of growth and revitalization in some of these areas, particularly downtown, but it’s limited. For 30 years, these neighborhoods have experienced poverty rates that significantly exceed the rate for Scott County as a whole; sometimes, by twice as much.

(In the second part of this report, coming next week, I will focus more on Davenport’s persistent poverty tracts.)

Who gets blamed for poverty?

How we talk about poverty in Iowa depends a lot on where the poor live, according to academics and experts I consulted.

Colin Gordon, a history professor at the University of Iowa, says there is a tendency to talk about rural poverty as something attached to a place. But the kind of poverty that exists in cities, like in these persistent poverty tracts, is attached to — and blamed on — people.

An assumption, Gordon says, is that people living in these urban areas have more economic options than those in rural areas, so if they don’t have a job, it’s their problem.

“You see this in the history of economic development in Iowa, of a lot of attention to rural opportunity zones or the equivalent,” Gordon says. “Even though I think it’s very misplaced policy, this accounts for a lot of the money thrown at things like ethanol plants.”

In larger cities, however, there are barriers to finding work, like transportation gaps. The availability of childcare also is a problem.

Gordon says that people who live in these persistently poor neighborhoods also suffer because of the “accumulation of disadvantage,” like lack of access to good jobs, educational opportunities, health care and the like.

“The circumstances can be overwhelming,” he says.

He adds that investments, principally in public schools, are important in these areas, as is putting funding into well-targeted economic development programs that create good-paying jobs there.

Advocates for the poor and middle class say that anti-poverty investments in these areas — as well as in other parts of the state — aren’t sufficient in Iowa, even though the state’s general fund surplus for fiscal year 2024 is expected to exceed $2 billion.

Lawmakers have kept a lid on spending, even as they’ve cut taxes, with most of the money going to the wealthy.

During the last session, the Legislature approved a budget that only spends 88% of revenues, according to most major media outlets. The legal limit is 99%.

The organization Common Good Iowa says the Legislature is being even more stingy. Actual spending is 82%, the group says. “There’s a lot of money on the table that the state could be using to support these areas, and I think it should get creative,” Sean Finn, a policy analyst at Common Good Iowa, says.

Some federal policies shortchange persistent poverty areas

There also are practices at the federal level that shortchange these smaller persistent poverty areas in favor of rural counties.

A provision in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 directed that a handful of USDA programs send 10% of its funds to persistent poverty counties. It was a unique approach at the time, aimed at helping poor areas, notably in the South. Since then, the idea has been expanded beyond rural development programs to other parts of the federal budget, according to a Congressional Research Service report, which focused on how such areas are defined.

However, what the Census Bureau report makes clear is that directing these federal funds only at persistent poverty counties means a lot of poor neighborhoods are being missed.

The report said that nationwide 9.1 million more people were living in persistent poverty census tracts than in persistent poverty counties.

That’s a lot of people who aren’t on policymakers’ maps.

Finn notes that some of these persistent poverty areas in Iowa correspond with neighborhoods where Black people have suffered from racist policies, such as those in the 1930s and beyond that restricted their access to home ownership financing.

Home ownership, he notes, is the main way to build wealth.

“Iowa needs to invest in these areas of persistent poverty,” he says. “Perhaps this looks like economic development funds, low- or no-interest loan programs for historically oppressed populations, or direct payments to those whose families were affected by Iowa’s racist laws.”

David Peters, a professor of rural sociology at Iowa State University, says he wasn’t surprised at the lack of persistent poverty counties in Iowa. The Upper Midwest, he says, doesn’t have the kind of broad-based structural characteristics — like lower education levels and economic barriers — that exist in the South and in Appalachia, where there are more impoverished counties.

He also cautions that some of Iowa’s persistent poverty areas include “temporary poor” like college students — or ex-prisoners living in transitional housing.

(The Census Bureau did exclude group quarters like prisons, jails and nursing homes from its report.)

Peters says it’s difficult to effectively aim resources at impoverished places, especially in Iowa, where poverty is more localized.

Grants and loans aimed at creating jobs may go to urban areas. But Peters says jobs that are created in poor areas often get nabbed up by people who don’t live there or who aren’t poor. Also, the money going to downtowns and adjacent commercial districts may be used to make improvements to the area, but they aren’t adequately focused on poor people, he adds.

Still, policymakers shouldn’t ignore these areas, Peters said. Local leaders, in particular, should, at the least, try to understand what it means to be poor in these areas, he said. “Is it a discrimination issue? Is it an education issue? Do the people living in these tracts have some sort of either criminal record, or drug addiction issues or mental health issues? It would be interesting to know.”

I was surprised when I saw this Census Bureau report.

We spend a lot of time in Iowa talking about rural decline, but not about high poverty urban areas.

I grew up in a small town in Iowa, and I’m pained to see how much has changed in rural parts of the state.

The governor’s rural task force is needed, as are investments like the nearly $150 million in federal money for broadband, which recently was made available through the state’s rural broadband grant program. However, as a Davenport resident for 30-plus years, I also see up close these urban areas where high levels of poverty have existed for decades.

These places need the attention of policymakers, too.

With the surplus the state maintains, this isn’t a problem that should be ignored, even if there are challenges to getting help into the hands of the people who need it the most.

Meanwhile, our congressional representatives also should take a closer look at ensuring federal funding aimed at persistently poor areas across the country doesn’t just stop at the county line. If it does, then tens of thousands of Iowans will continue to get shortchanged.

Coming next week: A closer look at the persistently poor areas of Davenport.

Along the Mississippi is a proud member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Please check out the work of my colleagues and consider subscribing to their work.

Laura Belin, Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Doug Burns: The Iowa Mercury, Carroll

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Stephanie Copley: It Was Never a Dress, Johnston

Art Cullen, Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca: Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Nik Heftman, The Seven Times, Los Angeles and Iowa

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Dana James: New Black Iowa, Des Moines

Fern Kupfer and Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Robert Leonard: Deep Midwest: Politics and Culture, Bussey

LettersfromIowans, Iowa

Tar Macias, Hola Iowa, Iowa

Darcy Maulsby: Keepin’ It Rural, Lake City

Kurt Meyer, Showing Up

Wini Moranville, Wini’s Food Stories, Des Moines

Pat Kinney, View from Cedar Valley, Waterloo

Kyle Munson: Kyle’s Main Street, Iowa

Jane Nguyen, The Asian Iowan, West Des Moines

John Naughton, My Life, in Color, Des Moines

Chuck Offenburger: Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger, Jefferson and Des Moines

Barry Piatt: Behind the Curtain, Washington, D.C.

Dave Price: Dave Price’s Perspective, Urbandale

Macey Spensley: The Midwest Creative

Larry Stone, Listening to the Land, Elkader

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Buggy Land, Kalona

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices

Cheryl Tevis, Unfinished Business, Boone County

Ed Tibbetts: Along the Mississippi, Davenport

Teresa Zilk: Talking Good, Des Moines

Also, please check out our alliance partner, Iowa Capital Dispatch. It provides hard-hitting news along with selected commentary by members of the Iowa Writers Collaborative.

Great article with the kind of research we no longer get from our newspaper. I was elected to the school board immediately following the closing of two small schools in the inner city of Davenport due to funding issues. Closing schools particularly K thru 5 kills neighborhoods. The state continues to underfund public education and last year made it worse by funding private religious schools for the most part. If we spent the money to keep schools open, provide assistance for home ownership in those neighborhoods, we would have a chance at improving our poverty issues significantly. Without that kind of investment, we will continue experiencing outcomes like increased crime.

I lived in an area of Cedar Rapids which was considered the "hood", for 37 years. I have since moved to rural Iowa where by circumstances, I live well. Your story is a reminder of my old home, uUnfortunately it leaves out Cedar Rapids. Many of the things you speak, people living in these areas can justify; they have seen it happen. It makes it very clear what politicians and develpers do in these areas which completely miss the mark. I was confronted by a man who represented acompany who were coming into our neighborhood with the help of all kinds of government money for "re-developing" our home turf. What they were doing was gutting our century old homes and rebuilding them like they were new. No more plaster and lath, no more old woodwork, all new plumbing, all new heating systems and air conditioning, all new bathrooms, all new kitchens, all new windows, all new siding and roofs. Then they would sell them to people looking for housing in the new "Hospital District" with deep discounts! The president of this organization and I met head to head so he could try and understand why I was bad mouthing his efforts to "improve" the neighborhood. I started off with a couple of questions, "how long have you lived in Cedar Rapids? followed by, "how long have you lived in this neighborhood?"

It started off OK, he had lived in Cedar Rapids 10 years, more than I had expected. After that, the reality of the situation came crashing in, he had never lived in the neighborhood! Worse, he couldn't see how that mattered! With no understanding of what I was getting at I attempted to show him what he could not see, and since we were right in the middle of the neighborhood at the time, I asked him to look across the street and tell me what he ssaw, he didn't understand the question. I zeroed in a bit and said , "Do you see anything wrong where the street joins the other one" He still didn't get the question. So to make it crystal clear, I explained what people would see who live here, that he couldn't see because he doesn't live here.

"People here don't have lots of options they ride the bus or they walk to get where they are going. Look at the cross walk, you didn't notice water sitting on each end of the cross walk? You also didn't notice the drains on both sides of the street three feet away that are getting no water from those low spots in the cross walk." He still didn't understand how that had anything to do with his project, or why the locals were not happy!

I tried to explain it to him in words he probably still didn't get, but I gave it a shot. "You walk in here and think you have all the answers to "our" problems. You have no idea how you are affecting the lives of people who have lived here for years and struggled to keep a house they could afford. With every house you completely rebuild you are increasing the property values and taxation for all your "neighbors". At the sametime you are getting butt loads of money to do exactly that, and pushing people out of their homes as a result. You see it as "cleaning up the neighborhood" we see it as you taking over. At least the people dealing drugs and shooting up the neighborhood weren't pushing us out!

This was a middle class neighborhood that went from here to the east and gradually became more wealthy the further east you went. All that changed when Robert Armstrong sold a lot on the far end of the neighborhood to a black doctor and instantly "white flight" happened. The large Methodist Church in the neighborhood became the epicenter and suddenly all those who could afford it moved to "Lovely Lane" Methodist church within two blocks of the soon to be built Kennedy High School! As that happened, the cities interest in the old neighborhood declined with the property values and suddenly our neighborhood became the dumping ground for every halfway house, every shelter house, every cheap apartment house and the zoning reflected that until we changed it by using the funding they were spending on the neighborhood against them! The Community Development Bloc Grant Program was being squandered on what the city wanted to do and we, as residents, were supposed to approve it, with a small chunk set aside for sidewalks and trees for us to decide where to put them! The trick to it all was the bloc grant program was established to help neighborhoods remain neighborhoods. So when we went with a petition to down zone the neighborhood, it passed without a whimper! My guess is they figured out we would take them to court if they didn't because they were not holding up their end of the bargain with the CDBG program. We could bring a suit against them for mis-appropriating the governments money if they were not doing what the grant proposed. The city didn't expend a dime of their own money in our neighborhood if they could keep from it.

The local Catholic Church had hired an organizer on a short term to try and improve the neighborhood and he was leaving, never to be replaced, unfortunately. So, without him, we quickly lost ground that we had dilligently worked to get power back in our hands. The city didn't waste time, they went to work trying to undo everything we had accomplished. Which had lead the city to this new attempt to cover up the failures they were resposible for in the first place by bringing in this current outfit that was pouring money into the neighborhood in an attempt to "erase the crime" and not talking about who else they were erasing!

Well, it is working! and now that criminal activity has been pushed out of the old neighborhood; shootings are happening all over town and rarely are they happening here! Our streets are still full of potholes, and water still settles in low spots in the cross walks, but property taxes are on the rise even if nothing gets done in the neighborhood, so all the power people are happy! Now I see new shelter houses in the neighborhood being established so things are getting back to "normal". The Police ignore calls, the street department does its best to make a joke out of the local streets, the engineering department doesn't bother with checking anything and life goes on! The President of the organization has moved on and some other monkey is probably in charge of the housing project. It is unfortunate, but no longer on my radar, although I sympatize with those who live there.