Note: In the first part of this two-part series, I wrote about persistent poverty areas in Iowa, and a new government report that shows how, despite the focus on rural poverty in this state, some of the most stubborn areas of economic hardship lie in urban centers.

In addition to rural Iowa, these urban pockets also need focused attention from policymakers — at the state and federal level.

In the second part of this report, I write in more detail about the persistent poverty areas of Davenport.

It’s about a two-mile stretch from west to east through some of Davenport’s poorest neighborhoods.

From Division Street on the west side to Bridge Avenue on the east, and from roughly 12th Street to the Mississippi River, Davenport’s persistent poverty neighborhoods are some of the oldest in the Quad-Cities.

The homes and buildings are aging. In some of these neighborhoods, houses mix with old commercial buildings — small manufacturers, machine shops, auto sales yards and the like.

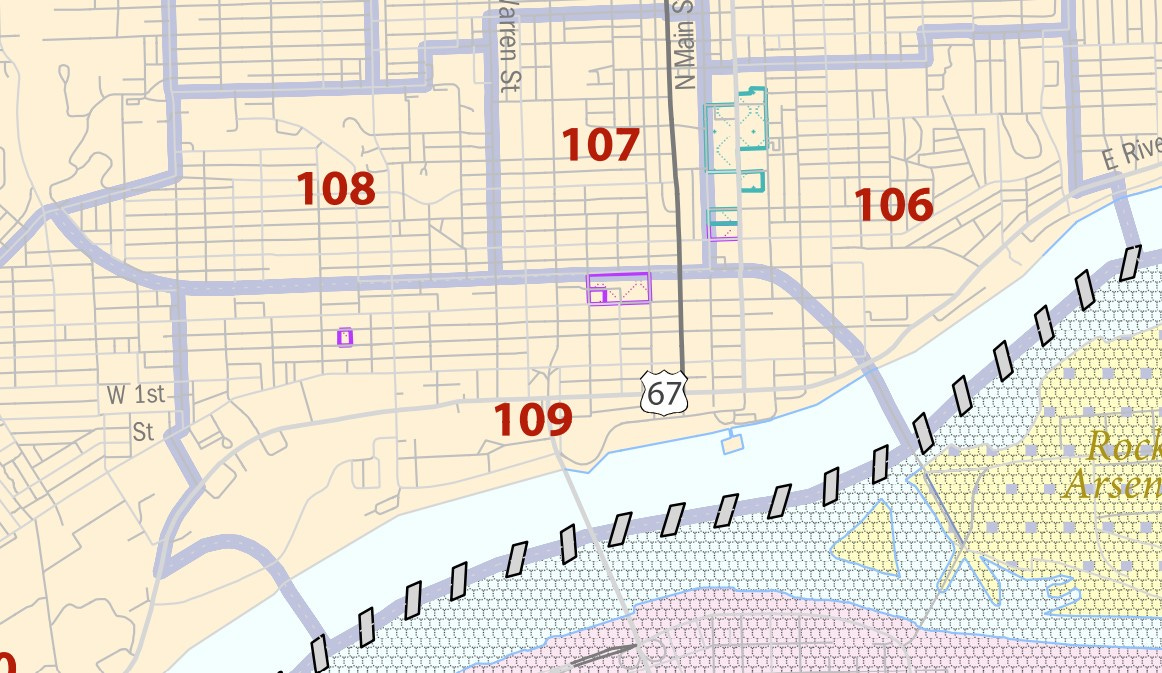

The population, while mostly white, is nonetheless home to a disproportionate percentage of the city’s Black population. And according to the US Census Bureau, the official poverty rate in these areas — technically census tracts 106, 107, 108 and 109 — has exceeded 20% for the 30 years between 1989 to 2019. These are what are called “persistent poverty” areas.

These four areas of Davenport are among the 39 persistently poor census tracts in the state of Iowa. (The others are mostly in urban areas, like Des Moines, Waterloo and Cedar Rapids.)

Nationwide, there are about 8,200 of these areas where poverty has gotten a stranglehold on a high percentage of the population and won’t let go. By contrast, there are about 341 counties that are defined as persistently poor.

A recent Census Bureau report cited longstanding research that says people living in high poverty areas have limited access to medical services, healthy and affordable food, a quality education and opportunities for civic engagement.

In Davenport, roughly 8,700 people live in these four persistently poor census tracts.

Over the years, there have been improvements in some of these areas, often with government assistance. For example, the City of Davenport’s DREAM home-ownership program aimed at restoring the neighborhoods in this general area, has provided grants to people willing to buy or fix up homes and stay.

In the downtown area, where a number of old warehouses and other buildings have been converted into apartments, there’s been noticeable improvement over the past 5-10 years.

A burgeoning entertainment and retail section also has sprouted there.

Still, outside of the downtown and selected pockets elsewhere, most of these persistently poor neighborhoods look little different than they did three decades ago. What’s more: A large share of their population remains in poverty.

These areas also are shrinking in population.

Davenport’s overall population doesn’t change much, but the differences between these persistently poor neighborhoods and the areas of the city where growth does occur are stark.

Consider a slice of northern Davenport between 53rd Street and Interstate-80 and Division Street and the eastern reaches of the city. The two census tracts (128.01 and 129.01) that encompass these areas grew by 23% between 2010 and 2020.

By comparison, the population of Davenport’s persistent poverty areas shrunk by 4%.

In 2010, those poor neighborhoods contained about 500 more people than that northern stretch of land; now, they have 1,900 fewer people. That’s a swing of 2,400 people in just 10 years.

There are many obstacles to growth — and to a route out of poverty — in these impoverished areas, but a big problem, according to housing advocates, is the lack of decent and affordable rental housing.

A 2020 report by the Quad-Cities Housing Cluster said that the Quad-Cities, including the Illinois side of the river, needs more than 6,600 units of housing for extremely low-income people in the community to afford a safe and decent place to live.

Leslie Kilgannon, director of the housing cluster, calls herself a “both/and” person who says the needs of rural Iowa should be addressed, but so too should the needs in central city neighborhoods where there is entrenched poverty.

“It’s hard for people to achieve balance, I suppose, but we do get a lot of talk about the rural areas in the state. But I don’t always think that those pockets of entrenched poverty get a lot of attention,” she says.

Kilgannon says she isn’t sure why this is, except that people living in these areas are “pretty far removed” from the political process.

A legacy of racism

It’s also notable where some of these persistent poverty tracts are.

Sean Finn, a policy analyst with the organization Common Good Iowa, says there is a clear tie between persistent poverty and government’s “racist policies” toward native populations and Black people.

He notes that some of these areas across Iowa correspond with neighborhoods that were redlined decades ago, when housing loans were steered away from neighborhoods with Black people.

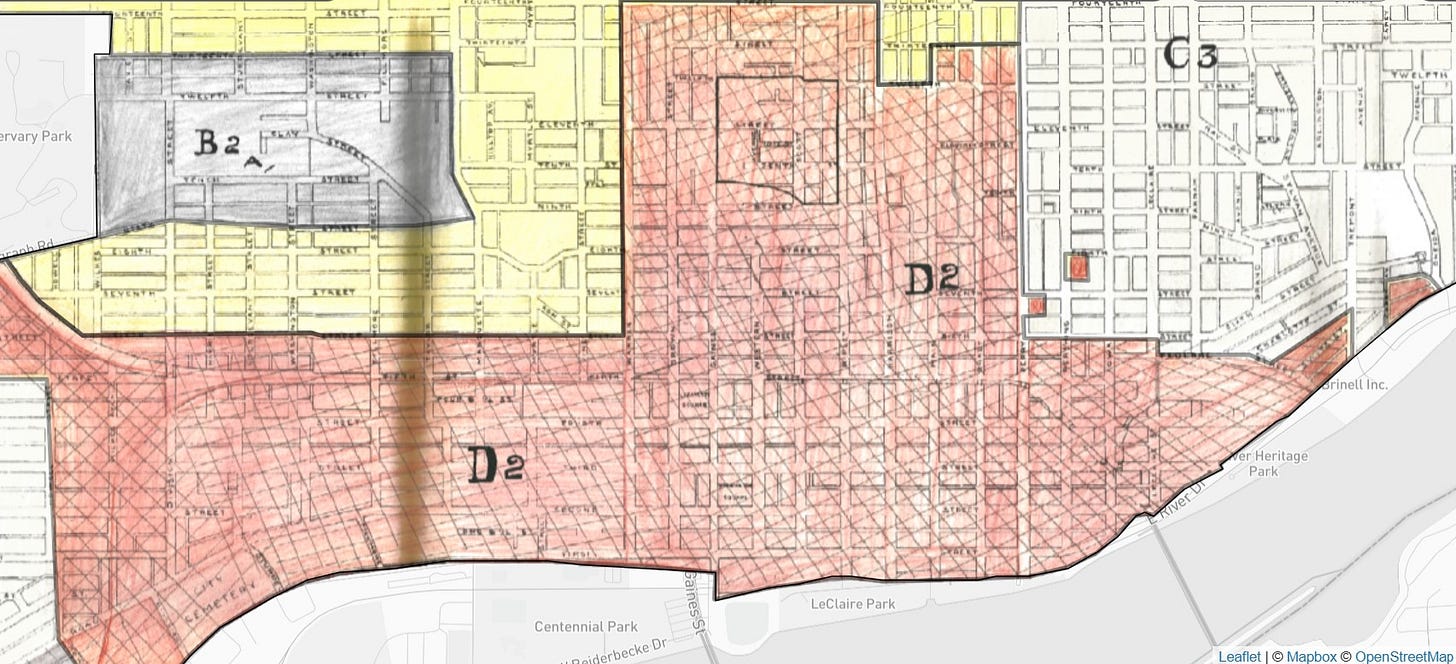

For years, scholars and journalists have pointed to the maps created by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, an agency founded during the Great Depression, as a key contributor to institutionalizing racist lending policies in the US. And while scholars have differed about how much HOLC maps themselves are to blame, what isn’t in doubt is that housing policies were discriminatory for a very long time, and the federal government played a substantive role in it.

In Davenport, some of those redlined areas on the old HOLC maps correspond with the persistent poverty census tracts that exist here today.

The long-term effects of discriminatory policies — and the question of what, if anything, should be done about it — greatly affect our political and cultural debates today.

Finn says Iowa must address this history. “The policy legacy really needs to be investigated,” he said.

It’s unlikely the Republican-run state government will move in this direction.

Lawmakers have instead put restrictions in place that critics say prevent the frank discussion of racism and inequality in this country.

David Peters, a rural sociology professor at Iowa State University, says it is important to realize some of the poor in persistent poverty areas of Iowa are in college and university towns and these areas also include housing for people transitioning from prison.

That means, as he puts it, some of the people living there are temporarily impoverished. (The Census Bureau study did exclude institutional group quarters, like nursing homes and prisons, from consideration in the poverty figures.)

Still, the poverty rates in these parts of Davenport are pretty high. The latest estimates released for 2021, which cover a 5-year period, put the poverty rate for these four census tracts at between 32% and 47%. Again, these are estimates, so they are subject to error.

Peters says lawmakers at the state and local level would do well to look closer at the poor people who live in these urban areas. Too often, he says, they’re “statistically invisible and they’re physically invisible.”

He has his doubts about place-based strategies in Iowa where poverty is highly localized, rather than those focused on the individual. Still, he says some placed-based investments in drug treatment and mental health services could help in areas where these factors affect poverty figures.

“It would be good for local planning and local poverty reduction efforts to target those areas … at least try to understand, what are the dynamics driving the persistent poverty in these particular communities?”

The struggles in rural Iowa are evident, and the state has made it clear these areas are getting help. Most of the experts and activists I talked to acknowledge rural Iowa needs assistance. But as this new Census Bureau report clearly documents, there also are other parts of Iowa that have struggled for a long time; they need help, too.

In the future, as Iowa decides where to devote its resources — as policymakers decide who is worthy of special assistance — perhaps greater attention could be paid to these areas.

Perhaps one day these neighborhoods won’t show up on a map signifying stubborn, long-lasting hardship.

Along the Mississippi is a proud member of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. Please visit the collaborative’s site and check out the work of my colleagues and consider subscribing to their work.

Also, pay a visit to our alliance partner, the Iowa Capital Dispatch. The Capital Dispatch provides hard-hitting news along with selected commentary by members of the Iowa Writers Collaborative.

Again, the "experts" rule, but no one really knows what works in a place where they have no knowledge. Largely people in charge have always been far removed from the poverty people face, they aren't in tune with the culture of many foreign born people who also find homes in these areas. Understanding poverty is not taught in a collge class room, not real American poverty because it is considered an anomaly to what they understand as middle class and better people. No one eats out of dumpsters in America, but they do, No one they know has slept under a bridge, but poor people do; living out of your car is somwthing reserved for all night drive in movies, not every night you can't find room in a shelter, like poor people do. Tragedy and turmoil are not everyday occurances for people "in charge" of poverty programs. They enforce rules and regulations which have no time for humanity or exceptions. Not everyone is a chisler or a cheat.

In Cedar Rapids, where the powerful look out for their own, a local bank president was out of a job since his bank got bought out, so the city offered him a job being in charge of "low rent housing". The first thing he did was initiate "credit checks" before renting to people! Imagine that, poor people with credit! In not tolong a period with no one passing the credit checks, vacancies werenot being filled and no rent was being paid as a result. Soon the cities low rent housing started to require repairs but no money was in the till. Unfortunately, our priveledged banker know what to do, since he was in charge and that was to take money from the Fedeeral Housing Projects that had set asside money for repairs on those Federal projects ONLY! Someone blew the whistle on the former bank president, and suddenly the whole city housing board resigned! No one was charged with malfeasence, absolutely nothing happened to any of that board! The City found a new pidgeon to put in charge that they could easily manipulate and suddenly as a result a brand new warehouse that had been converted to over 70 units of low income housing using 4 million dollars of federal money was to expensive for the low income housing board to operate and the city sold it to the company that converted a warehouse two feet away into high dollar condominiums. Not only did they unload the building on them, but out of "gratitude" gave them the adjoining park and garanteed them "Streetscaping". When I asked why they had not offered "Streetscaping" to the rest of the "New Bo" Neighborhood businesses, they told me none of the businesses agreed in writing to do a cost share. When I checked with the President of the Neighborhood he told me that all the paperwork had been filed with the city months ago including the paperwork on the cost sharing. I called the city back and told them what I had learned. Suddenly a meeting between the city and the President of teh Neighborhood happened and "Streetscaping" was offered to all the businesses! So, the facts are out there, the wealthy take advantage of the poor, the same with landlords, and even grocery stores who charge more and blame it on shop lifting and the cost of insurance. Lack of local work that pays well and police who follow proceedures that target people of color, all things big and little that happen in and around these neighborhoods are preventable, if there is a real push to make it happen.

Affordable housing is critical element for our educational system. Children are moving in and out of different schools in Iowa and Illinois as much as 4 or 5 times a year, because their parents are evicted and can't pay the rent. As soon as a reading teacher makes progress with a child, they leave, and another teacher starts all over again. If you can't read, you can't succeed and the connection to poverty is obvious.